As of April 15, the Covid-19 pandemic has infected almost 2,000,984 people in 185 countries, resulting in more than 128,000 deaths. Pakistan had its first two confirmed cases on February 26. By April 15, the number of confirmed cases had crossed 6,000 and 107 deaths had been reported.

The medical emergency has transformed into a labour market crisis due to the resulting demand and supply shocks. In a bid to flatten the curve of the spread of pandemic, the federal government announced the closure of all educational institutions throughout the country. Provincial lockdowns, initiated on March 23, have now been extended until April 28.

Before we discuss the labour market issues in detail, let’s have a quick look at Pakistan’s labour market. Pakistan has a population of 207 million people, of which 63.4 million are engaged in the labour force (aged 15 years and above).

The services sector is the largest employer engaging 38 percent of the labour force, followed by agriculture (37 percent) and the industrial sector (25 percent). Of the 59.8 million employed labour force, Punjab (60 percent) has the highest share followed by Sindh (23 percent), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (12 percent), Balochistan (4 percent) and Islamabad (1.15 percent). Only 10.6 million non-agricultural workers (28 percent) work in the formal sector with labour law protections. The remaining 72 percent are toiling in the informal sector.

Data further show that of the 25.7 million wage employees, only 14.6 million are paid monthly. Remaining 11 million are either daily wagers (5 million), weekly earners (4 million) or piece-rated workers (1.8 million).

Due to the closures, many of these casually and irregularly paid workers have lost their jobs. Generally, unemployed would engage in self-employment or move to another location. However, considering the imminent lockdowns and curfew-like situations, this is no longer possible.

While provincial governments and the Islamabad administration have instructed employers not to terminate the employment contracts of workers during the lockdown, 74 percent (19 million) of the wage employees are working without any contract/appointment letters. Hence, the above instructions can be easily flouted.

Who is affected by the pandemic?

The Centre for Labour Research has estimated job disruptions for around 21 million workers in the country on account of the Covid induced lockdowns. The sectors, facing the most economic risk, are construction, manufacturing, accommodation and food services, wholesale and retail trade, transport and storage, and real estate and business activities. All at-risk sectors are labour-intensive and employ 28.45 million workers, most of which are low-paid and low-skilled. The share of total employment in these high-risk sectors is 47 percent of total employment in the country.

As regards enterprises, the most affected are microenterprises. The private non-agriculture sector engages 33.36 million workers. Of these, 26.89 million are working in microenterprises employing ten or fewer workers. This is equivalent of 45 percent of the total employed labour force and 81 percent of the non-agricultural private sector workforce

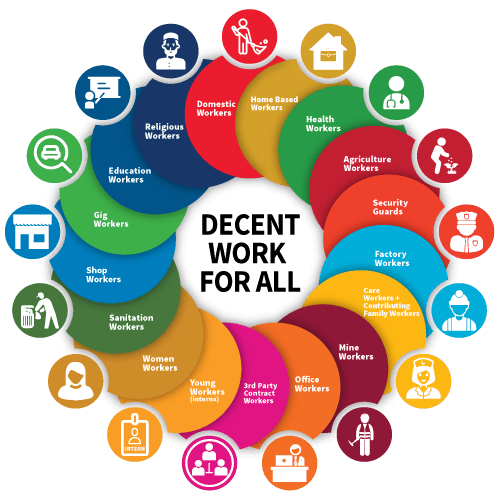

Those particularly vulnerable under the current situation are women workers, elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions, young workers, persons with disabilities, informal economy workers and self-employed workers like street vendors, taxi drivers and gig workers engaged with different digital labour platforms. Covid has affected livelihoods of domestic workers (8.5 million), home-based workers (4.8 million) as well as those working on roads, including street vendors (4 million).

The gig or platform economy workers, especially those providing geographically tethered services like transportation (Uber and Careem), delivery of items (Bykea) and domestic work (Mauqa, Ghar Par) are the worst hit.

Considering the fact that food delivery is permitted by the provincial governments even during the lockdowns, gig workers working with delivery platforms like Foodpanda, Careem, Uber, and Bykea are on the front lines of this crisis. They are delivering food to those self-isolating or practising social distancing.

While government-announced lockdowns in provinces have protected the jobs of “workers” in the formal sector requiring employers to pay full wages and not terminate any, the so-called “independent contractors” do not have access to any of these protections. Research already indicates that domestic workers, delivery persons (couriers), garbage collectors, and janitors, all part of the growing gig economy, are at the highest risk of being exposed to coronavirus.

Self-employed workers, especially gig workers, are facing the tough choice between exposure to the pandemic (getting sick and infecting families) or exposure to starvation (by not working and losing income).

What government can do?

The following actions are recommended to ameliorate the pernicious effects of Covid pandemic on the labour market:

Implement WHO guidelines at workplaces to protect workers and minimise the direct contact. Work councils can play a role in awareness-raising on social distancing and other hygiene measures at workplaces. Health and safety provisions from Factories legislation or OSH legislation should be applied earnestly.

Protect employment through incentives

The economic sectors and enterprises negatively impacted by the coronavirus, especially in the manufacturing and services sectors, should be protected through incentive measures. Governments should ensure that workers suffer no wage losses due to quarantine or isolation.

The government can reduce or waive payroll taxes (PESSI, EOBI) for three months (March-May 2020) to the enterprises that retain their workforce. The government may also announce time-bound tax relief measures for enterprises who announce job-sharing schemes.

Provide unemployment benefits

The government can start giving unemployment benefits (at least equivalent to a minimum wage of Rs 17,500 per month) to the unemployed and initiate public employment programmes. The local government system can help identify individuals who lost their employment due to the enterprise closures or cancellation of public events.

On March 30, the Economic Coordination Committee approved Rs 200 billion of cash assistance for the daily wagers working in the formal industrial sector and who had been laid off as a result of Covid-19 outbreak. This amount can be used to initiate a basic unemployment benefits programme. All these workers, irrespective of their work status, must be registered with the PESSIs and the EOBI. Once this pandemic is over, special contributory social insurance schemes can be launched for self-employed, informal and agriculture sector workers.

Make social protection a fundamental right

Recently, the Ehsaas Policy Statement mentioned the government’s aspiration to introduce a new constitutional amendment to move Article 38(d) from the Principles of Policy section into the Fundamental Rights section. This change would make provision of food, clothing, housing, education and medical relief for citizens who cannot earn a livelihood due to infirmity, sickness or unemployment, a state responsibility. The time to introduce such constitutional change is now since healthcare, sickness benefits and unemployment benefits must be universally accessible. The federal government has already announced an Emergency Cash Programme of Rs 12,000 per family for 12 million families.

Give legal cover to the teleworking and flexible worktime arrangements, not only for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic but also for later times to reconcile work and family. Social distancing, a major tactic to curb the spread of coronavirus, can be done through telework. While some jobs, by their very nature, are difficult or impossible to do without the physical presence of worker at the worksite (like food and beverage workers, construction workers, law enforcement agencies), knowledge workers especially financial analysts, accountants, lawyers, software designers, scientists and engineers should have work from home provisions.

Enact new legislation for microenterprises, employing ten or fewer workers. LFS 2018 already shows that 26.89 million are working in the micro-enterprises in the non-agricultural sector. A simplified single labour code for micro-enterprises, with fewer requirements and ease of compliance, must be enacted at the earliest.

Regulate the gig economy

Deregulation of the gig economy is hurting the economy and society as a whole by producing a whole generation of unprotected workers. Gig economy workers are part of a large informal economy without access to any social protection benefits. Requiring digital labour platforms to register their workers aka independent contractors with social security institutions and the EOBI could be the first step in that direction.

Basic labour protections, adequate living wages, decent working hours, social protection and safe workplaces should be available to everyone irrespective of contract/employment status. Social protection should not be a luxury; it should be available to everyone.

This article was published on The News on Sunday on 19th April 2020