One hundred and ninety three states decided in September 2015 to adopt a set of 17 goals to end poverty and ensure decent work as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Each goal has specific targets to be achieved over 15 years. There are 169 targets and 232 indicators listed under these 17 goals.

Unlike the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), where full employment and decent work were addressed through the inclusion of a new target (Target 1B) in 2007 (six years after the start of MDGs in 2001), Goal 8 under SDGs focuses on the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth that leads to employment and decent work for all. This has not made many happy either. The linking of economic growth and decent work under Goal 8 has been criticised as the relegation of decent work to being a mere dividend of economic growth.

Despite this criticism, thanks to the global financial crisis of 2008 and now Covid-19-induced labour market crisis, employment has gained centre-stage. Employment and employment-related issues are also referred to in other goals.

Target 8.8 refers explicitly to the protection of labour rights and promotion of safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment. While Target 8.8 talks about protection of all labour rights, Indicator 8.8.2 is concerned only with the national compliance of freedom of association and collective bargaining rights.

There is no doubt that the freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining are enabling rights. These not only have a direct bearing on labour and economic outcomes but also help in cementing democracy in a country, as is evident in the case of National Dialogue Quartet of Tunisia which was awarded Nobel Prize in 2014 for its support to democracy after the Jasmine Revolution. Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) was one of the four organisations that were awarded the Nobel Prize.

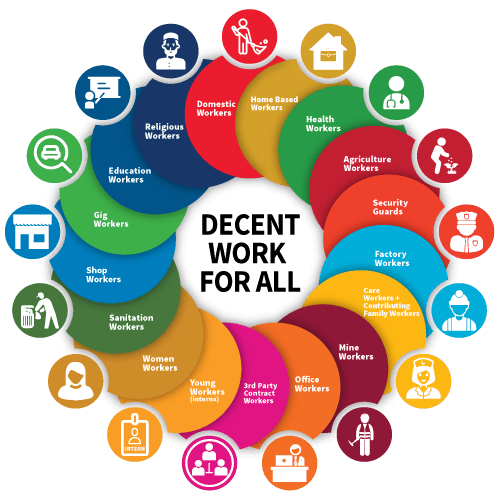

However, as required under Target 8.8, protection of labour rights as a whole has to be ensured, including for those in precarious employment, the most recent form of which is gig economy. Instead of focusing only on trade union rights, all workplace rights can and should be measured and monitored both in law and practice.

While consultations on SDGs are said to have been unprecedented, SDG indicators have not been part of the global consultation process; rather these were selected and finalised by a group of experts in March 2017. Implementation and achievement of Target 8.8 depend on the availability of data on labour laws and labour practices. Labour rights are covered under many indices and databases.

Some of these indices were created by the ILO while others include World Bank’s Doing Business Indicators (Employing Workers Index-EWI), Women, Business and Law Database, World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (Labour Market Efficiency Pillar), Harvard/NBER Global Labour Survey and International Social Security Association. While the International Labour Organisation is the lead agency for indicator 8.8.2, some work is already in progress on the issue.

ITUC Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights covers trade union rights. The ITUC Global Rights Index, though a misnomer, measures only trade union rights using a set of 97 indicators. The Centre for Global Workers’ Rights under Penn State University has also worked on the Labour Rights Indicators measuring compliance both in law and practice for freedom of association and collective bargaining rights over a set of 108 indicators. Same indicators or evaluation criteria have been proposed by the ILO for measuring progress under SDG Indicator 8.8.2.

Despite this glut of indices on labour rights, experts at WageIndicator Foundation and Centre for Labour Research have been working on the idea of a new de jure index, i.e., Labour Rights Index. While various targets under SDG 8 focus on statistical data, none of those targets and indicators delves into the de jure labour rights protections as required under Target 8.8. The Index, based on 10 indicators and 46 evaluation criteria, compares labour legislation in 105 countries.

The topics cover fundamental workers’ rights (right to trade union and elimination of gender discrimination, child labour and bonded labour), fair remuneration, decent working hours, employment security, social protection (access to the living wage, unemployment, old age, disability and survivor benefits and health insurance), work-life balance for workers with family responsibilities and access to safe and healthy workplaces.

The Index is built on Decent Work Checks which have detailed explanations on de jure provisions on various workplace rights under national labour law. None of the above-referred indices is as comprehensive and detailed as the proposed Labour Rights Index.

While many would argue against building another index focusing only on de jure labour market institutions and provisions (namely existence of large informal sector, in developing countries, non-compliance coupled with the tepid and lackluster implementation of labour laws), well-drafted and inclusive laws (with least exclusions) are still a pre-condition for attaining decent work. Well-drafted laws provide clear and explicit answers to difficult and perplexing questions.

This point is quite lucidly summed up in the 2010 World Social Security Report which is of the view that even the widest and most expansive legal foundations cannot achieve the desired outcomes if these are not enforced and backed by sufficient resources. Nonetheless, strong legal foundations are a pre-condition for securing higher provisions and resources. There is not a single situation where a country provides generous benefits without a comprehensive legal basis.

Similar points have been raised by Botero et al that formal rules, although different from “on the ground” situation, still matter a lot. Botero’s work forms the basis of Doing Business Indicators by the World Bank. Research clearly indicates that in the absence of legislation, even the wealthiest country in the world, i.e., the United States of America, is unable to ensure decent working conditions for a majority of its citizens.

As explained by Heymann and Earle, “laws indicate a state’s commitment to its people, lead to change by shaping public attitudes, encourage government follow-up through inspection and implementation of the law and allow court action for enforcement”.

The proposed Labour Rights Index also covers the regulation of the gig economy as one of the evaluation criteria and gives a positive score to a country where gig workers are not treated as merely independent contractors. Other than California (USA), no country or state has enacted legislation to protect the rights of these precarious workers.

The results and insights from this upcoming comparative Index can be used to bring much-needed labour legislation reforms in various countries. Universal labour guarantees or basic labour protections should be available to everyone which essentially means that all workers, regardless of their contractual arrangement or employment status, should enjoy fundamental workers’ rights (freedom of association and right to collective bargaining, non-discrimination, no forced or child labour) an adequate living wage, maximum limits on working hours, safety and health at work, and access to the social protection system.

Progress on Target 8.8, requiring protection of labour rights for all workers, including those in precarious employment, can be measured only through the comprehensive Labour Rights Index. In view of the labour market havoc wreaked by the Covid-19, this is the most opportune time to talk with the protection of all labour rights and measure progress of member countries.

In the words of the California attorney general, “Sometimes it takes a pandemic to shake us into realising what that (lacking basic labour protections) really means and who suffers the consequences.” It is time to measure all countries’ progress on all labour protections instead of merely focusing on trade union rights under SDG Indicator 8.8.2.

This article was published in TNS on 31st May 2020