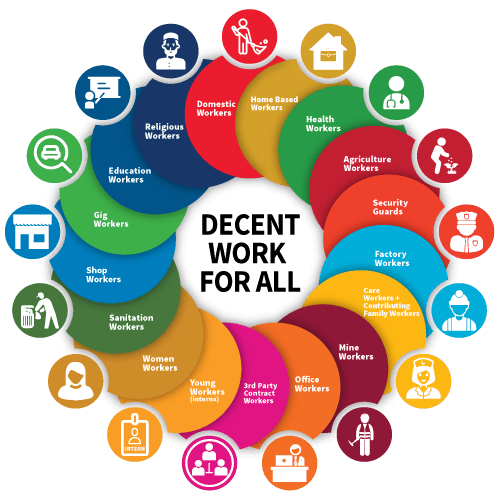

Pakistan has 68.75 million workers. More than half of the working-age population does not join the labour force due to one of the lowest female labour force participation rates in the world (21.5 percent) and high youth NEET (not in education, employment or training) rates hovering for years around 30 percent. Nearly 70 percent of Pakistan’s population is under 30 years of age. In its 100-day plan, the incumbent government had aimed to create 10 million jobs in five years.

In recent years, Pakistan has experienced growth in the platform or gig economy, a new form of work where digital labour platforms bring together providers of services (workers) and users or customers. However, there is a fundamental distinction in platform work: on-location (like ride-hailing, delivery, domestic and personal care services) or online (software development, data entry, translation work, digital design work, etc).

All the major cities in Pakistan have recently seen a proliferation of ride-hailing and delivery riders that have become nearly omnipresent. Platforms claim that they are technology companies merely bringing together the service providers and users. They simplify transactions between the parties by reducing transaction costs (by connecting them and setting rates) and managing information asymmetries while standardising the worker and user experience and nudging platform participants’ behaviour.

There is an evident data deficiency regarding the service providers affiliated with on-location platforms and the number of users accessing these services. While platforms do reveal, at times, the rides or deliveries done in a year, they remain stingy on sharing data of active service providers. The labour force survey also does not cover the new non-traditional forms of work, including platform work.

Despite these data deficiencies, the Centre for Labour Research estimates that on-location platforms have an active workforce of nearly half a million workers. Due to the gradual increase in urban population and the urban lifestyle (though currently, the urban population is 37 percent in Pakistan), there is a growing demand for food delivery, ride-hailing (primarily due to a lack of public transport system) and domestic services.

Although there is high turnover in the platform economy, the supply of labour is higher, and active service providers keep increasing due to ease of entry and various enticing measures adopted by the platforms. Our research indicated that most workers in food delivery are young, while ride-hailing has workers of all ages. We also learnt that most of the interviewed workers treat platform work as their primary or only source of income. Less than 10 percent of workers treated platform work as a secondary source.

The regulatory institutions, not only in Pakistan but also the world over, have not kept up with the change in the employment landscape. The digital labour platforms treat these workers as self-employed, considering their so-called autonomy. However, quite like the formal employment relationships, the platforms unilaterally regulate employment and working conditions while using algorithmic management tools to monitor, evaluate work and impose sanctions where needed. While platforms claim that workers can choose to work through the platform, these workers have no bargaining power and accept the terms imposed by the platforms.

This misclassification in employment status (considering them independent contractors instead of workers) excludes them from the purview of labour laws and associated rights. The government has so far adopted a laissez-faire approach in regulating platform work. The provincial governments tried to implement motor vehicle legislation on ride-hailing platforms some years ago; however, no relevant action was taken.

Although there is high turnover in the platform economy, the supply of labour is higher, and active service providers keep increasing due to ease of entry and various enticing measures adopted by the platforms.

Unlike other forms of work in the informal sector, the platform economy is well documented. The digital labour platforms are scrimping millions of rupees per month by treating the platform workers as self-employed, i.e., expendables. The employment misclassification not only robs nearly half a million workers of various labour law protections but also allows evasion of employment-related social protection levies and contributions worth billions of rupees per annum.

Consider this example to understand the cost of misclassification. The labour legislation in Pakistan requires employers to register workers with Provincial Employees’ Social Security Institutions (PESSIs) and Employees Old-age Benefits Institutions (EOBI).

The total contribution rate is 11 percent of a worker’s wage. If the worker’s wage is treated as the currently applicable minimum wage (Rs 20,000 per month), the platform contribution is 2,200 per month per active worker. If we calculate this contribution evasion for 500,000 workers, the amount is Rs 13.2 billion per annum.

This amount could be used to provide workers with social protection in case of sickness, occupational accidents, health care to workers and their families, and support during Covid-induced lockdowns when the platform workers had to bear the brunt since government protection (prohibiting employers from dismissing workers during covid lockdowns) did not apply to them. Placing digital labour platforms under labour law jurisdiction expands the economy’s tax base and makes the employment-related social protection system sustainable.

But this is not only about social contributions. The misclassification deprives platform workers of the right to minimum wage and a decent standard of living, the right to overtime pay, the right to annual leave, the right to sick leave, the right to equal treatment, and most importantly, the right to unionise and bargain collectively.

The Centre for Labour Research has been working in collaboration with the Wage Indicator Foundation and the Fairwork Foundation to draft legislation protecting the rights of platform workers in the country. The draft legislation addresses the major concerns about platform work in Pakistan. It eliminates the chances for worker misclassification by setting various conditions and ensures transparency and accountability in algorithmic management.

While legislation in India requires social security benefits for the platforms (still to be effective, though), the draft legislation gives platform workers all workplace rights, including the right to minimum wage, working hour restrictions and premium wage payments for work on public holidays, during night hours and inclement weather, right to various kinds of leave including but not limited to annual leave, sick leave, maternity leave, social protection and various cash benefits from the PESSIs and EOBI including old-age pensions, safety and health protection of the platform workers, protection from multiple forms of discrimination and harassment including sexual harassment, data protection and data portability rights, mandatory works councils requiring social dialogue at the level of the platform, and most of all the right to unionise and bargain collectively.

Under the draft legislation, the platforms will be required to register and deposit their workers’ contributions to the social protection bodies. The platforms will also be required to share the data on platform workers with the government. Given the Supreme Court of Pakistan’s verdict on contractors’ workers, the draft legislation includes contractors and sub-contractors used by the digital labour platforms in the definition of employer. The draft legislation covers only on-location platforms since the online platform workers are already covered under the Islamabad Capital Territory Homebased Workers Bill, passed by the federal cabinet last year.

While it is essential to recognise the job creation potential of the digital labour platforms, it is also imperative that people working through these platforms have decent working conditions. Enacting legislation for the protection of platform workers is not only in line with the Constitution (Article 25 guaranteeing equality before the law and equal protection of the law), it also conforms to the Riyasat-i-Madina model that the government aspires to.

Moreover, under the Objectives Resolution, which is part of the Constitution, the legislature must ensure an egalitarian society based on the Islamic concept of fair play and social justice. Therefore, the legislature should act now and bring the platform workers under the protection of labour laws.

This article was published in TNS on 19th December 2021 check it here