COVID-19 and Labour Market

Covid-19 and Labour Market Implications for Pakistan

.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) has led to a labour market crisis in Pakistan. The services sector is the hardest hit sector, especially tourism and hospitality, education and transport sectors. Daily wage, piece rated workers as well as self-employed workers are the worst affected.

- There are nearly 14 million confirmed cases of Coronavirus pandemic worldwide….

- Nearly 600,000 have lost lives in at least 185 countries…

- Pakistan also has nearly 251,000 confirmed cases of which 5,568 have already passed away.

- Services sector is the hardest hit sector, especially tourism and hospitality, education and transport sectors.

- Daily wage, piece rated workers as well as self-employed workers are the worst affected.

- Government of Pakistan needs to take certain action to limit the negative impact of COVID-19 on labour markets by protecting the already marginalised and vulnerable, i.e., young workers, elderly, women, persons with disabilities and daily wagers.

There are nearly 14 million confirmed cases of Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) worldwide. Nearly 600,000 have lost lives in at least 185 countries. Pakistan also has more than 251,000 confirmed cases of which 5,568 have already passed away.

Provincial governments are taking actions by closing down wedding halls, restaurants, hotels and shopping malls. The Federal Government announced the closure of all schools, colleges, universities and madrassahs throughout the country till 5 April 2020. Provincial governments initiated strict lockdowns from 23 March 2020.

The medical emergency has transformed into a labour market crisis due to the resulting demand and supply shocks. At a global level, ILO estimates a surge in global unemployment of between 5.3 million (“low” scenario) to 24.7 million (“high” scenario) from a base level of 188 million in 2019. The estimated reduction in working hours due to COVID, by 6.7 percent in the second quarter of 2020, is equivalent to 195 million full time workers. Of the total 3.5 billion labour force, more than 80% are affected by workplace closures.

Envisioning different scenarios, it is estimated that structural unemployment, due to the slowing down of the economy in Pakistan, will range from 3 million to 5 million. The temporary unemployment due to the lockdown is estimated at 10.5 million workers, including daily wage and contract/casual workers in establishments. Centre for Labour Research estimates job-disruptions for around 21 million workers in the country.

Similarly, there are estimates that 9 to 15 million people will fall below the poverty line due to COVID-19 induced crisis. Estimates from PIDE depict a bleaker a picture, forecasting 20 million to 70 million persons falling below the poverty line. The poverty line was last estimated for 2015-16, which indicated that 24.3% of the population was living below the poverty line.

In a bid to flatten the curve’ of the spread of pandemic COVID-19, the Federal Government announced the closure of all schools, colleges, universities and madrassahs throughout the country. Provincial lockdowns, initiated on 23 March, have now been extended to 28 April 2020.

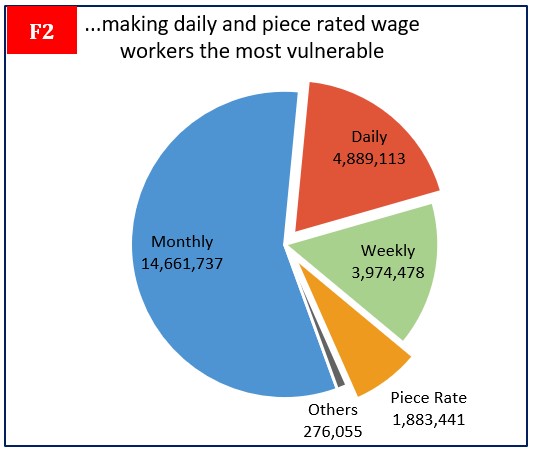

Other than being a medical emergency, COVID-19 is also becoming a labour market emergency as many are losing their jobs. The more vulnerable are daily wage labourers and all such workers who are either working on a piece-rate basis and those working with on-demand service providers like Uber, Careem, Mauqua, Gharpar, etc. ILO has estimated that the “economic and labour crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic could increase global unemployment by 5 million to 25 million”.

Best Practices from Around the Word

Labour Market Landscape in Pakistan

Before we discuss the labour market issues in detail, let’s have a quick look at Pakistan’s labour market. Pakistan has a population of 207 million persons, of which 63.4 million are engaged in the labour force (aged 15 years and above). The unemployment rate is nearly 6% (3.6 million).

The services sector is the largest employer engaging 38% of the labour force, followed by agriculture (37%) and the industrial sector (25%). Of the 59.8 million employed labour force, Punjab (60%) has the highest share followed by Sindh (23%), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (12%), Balochistan (4%) and Islamabad (1.15%).

A labour force is categorized into the following four categories: wage employees, own-account workers (self-employed), unpaid family workers and employers. Pakistan’s employed labour force (59.8 million) is composed of employees (43% or 25.7 million), self-employed (36%), unpaid family workers (20%) and employers (1.4%). Only 10.6 million non-agricultural workers (28%) work in the formal sector with labour law protections. The remaining 72% are toiling in the informal sector.

Data further show that of the 25.7 million wage employees, only 14.6 are monthly paid workers. Remaining 11 million are either daily wagers (5 million), weekly earners (4 million) and piece-rated workers (1.8 million). To compare workers by the periodicity of wage payment, please refer to the F-3.

Due to the closures, many of these casually and irregularly paid workers have lost their jobs. Generally, unemployed would engage in self-employment or move to another location. However, considering the imminent lockdowns and curfew-like situations, this might also not be possible.

While provincial government, including Islamabad, have instructed employers not to terminate the employment contracts of workers during the lockdown, 74% (19 million) of the wage employees are working without any contract/appointment letters. Hence, the above instructions can be easily flouted. Only 5.3 million workers have permanent employment contracts and pensionable employment, a considerable majority of which is working in the public sector and large private sector enterprises.

Who is affected by the pandemic?

Sectoral Analysis

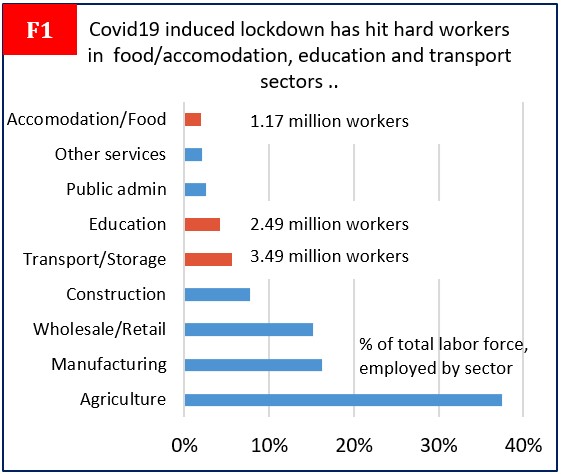

The sectors, facing the most economic risk, are construction, manufacturing, accommodation and food services, wholesale and retail trade, transport and storage, and real estate and business activities. All these sectors are labour intensive and employ 28.45 million workers, most of which are low-paid and low-skilled workers. The share of total employment in these high-risk sectors is 47% of total employment in the country.

The services sector is the worst hit due to the COVID induced lockdowns in the country. All sub-sectors, be it food and accommodation services (tourism and hospitality industry), educational institutions, retail, and the transportation sector, have been the worst hit.

The Labour Force Survey of 2018 indicates that 1.18 million workers are engaged in the food and accommodation sector. Those working in the education sector are 2.5 million, while the transport and storage sector alone employs 3.5 million. The construction sector, employing 4.7 million workers, has come to a grinding halt owing to the lockdown and recommended social distancing.[1] Construction is the most labour intensive sector and most workers engaged in the sector are daily wage workers or employed on a piece-rate basis. Manufacturing sector[2], also engaging 9.7 million workers, is impacted by the lockdown and cancellation/postponement of export orders. Due to the restrictions imposed on imports by the countries as well as cancellation of export orders for Pakistani goods has impacted the manufacturing sector as well. The construction sector is also hit by the lockdown as it

Agriculture, to this moment, remains largely unaffected due to the government’s policy of allowing movement of goods across the country, including agricultural produce. Similarly, the government has allowed food and beverage manufacturing units, pharmaceuticals as well as seeds and pesticides unit to continue working even during the lockdown. There can be issues of food security due to border closures. Workers in the sector and the whole food supply chain will be impacted if the virus spreads further into rural areas.

Total expected job disruption is 21.24 million of which 77% (16.49) million is working in the “at-risk” sectors including construction; accommodation and food service activities; manufacturing; transport, storage and communication; real estate, business and administrative activities; and wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

[1] Prime Minister of Pakistan, on 03 April 2020, announced that construction sector will be given the status of an industry and incentives for investors and businessmen to mitigate the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak. Construction Industry Development Board will also be set up to support the sector. Prime Minister further said that industries connected to construction will continue to function even during the lockdown. This will not only positively impact 4.7 million workers, employed directly in the construction sector but millions others, employed in allied industries. Centre for Labour Research has prepared a policy brief on how to make construction work decent. The main policy recommendations include enactment of separate legislation for the construction sector, fixing the public sector contracting system and imposing a social protection levy on commercial and residential construction.

[2] Food, beverage and pharmaceutical manufacturing firms are allowed to work during all provincial lockdowns. LFS 2018 indicates that there are 2.81 million workers employed in this sector. Please refer to Table 10 in Annex. Government of Punjab has allowed the following industries to work during the extended lockdown: textile industries (36 units); sports goods (10 units); surgical/medical instruments (07 units); auto parts manufacturers (03 units); pharmaceutical (25 units); leather and leather garments (22 units); fruits and vegetables (07 units); and meat and meat products (08 units), notification dated 03 April 2020, by Home Department, Government of Punjab. Further enterprises have been exempted in a notification dated 04 April 2020.

Enterprise Level Analysis

COVID-19 is both a supply-side and demand-side shock and is poised to impact, micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) the most.[1] Most of the enterprises in Pakistan are microenterprises, employing less than ten workers. These are also the enterprises which would find it challenging to comply with cumbersome legislative commandments of retaining employees during lockdowns. The private non-agriculture sector engages 33.36 million workforce. Of these, 26.89 million are working in microenterprises employing ten or fewer workers. This is equivalent to 45% of the total employed labour force and 81% of the non-agricultural private sector workforce. Interestingly, this number (26.89 million) is nearly equal to the non-agricultural informal sector (26.84), which is equivalent to 72% of the non-agricultural workforce. This shows that microenterprises are essentially informal sector enterprises, and most of the employment in the informal sector can be attributed to the microenterprises.

SMEs, being more labour intensive, are considered an engine for employment generation; however, no reliable and updated estimates are available. According to SMEDA, 3.25 million MSMEs[2] constitute nearly 90% of all the enterprises in Pakistan; employ 80% of the non-agricultural labour force; and their share in the annual GDP is 40%, approximately.[3] Most (97%) of these enterprises are under individual ownership and hence mainly working in the informal sector. Draft National SME Policy 2019 states that there are around 3.8 million small and medium enterprises in Pakistan wherein commercial and retail shops have the highest share (1.8 million), followed by the services sector (1.2 million) and industrial sector (0.8 million).

Do the MSMEs create enough and decent jobs? The entrepreneurial attitude can be observed through LFS, which indicates that only 1.4% of the total employed labour force opted to be an employer.[4] Even if we took the number of 3.8 million MSMEs and put it together with 33.36 million non-agricultural private-sector workers, the average number of workers per MSME is only nine, which places it in the informal sector. While start-ups and MSMEs do lead to job creation but their impact at the macro level is small as most of the start-ups vanish in the second and third year of business.

Research has shown that youth-led enterprises are struggling to survive in the face of economic shock caused by the pandemic. There is reduced customer demand and supply chain disruptions. A global survey indicated that one-third of the youth-led enterprises had to lay off its staff while a quarter had to reduce wages.[5]

The relevant SME clusters in Pakistan include readymade garments cluster (Lahore), footwear cluster (Lahore), Auto-parts cluster (Lahore), Surgical cluster (Lahore), and Leather industry (Sialkot). Government of Punjab, in its notification dated 03 April 2020, has exempted these clusters from lockdown.

[1] The enterprise level analysis is based on 2005 Census of Economic Establishment, State of SME Finance Article by SMEDA, and Labour Force Survey 2018.

[2] These numbers are based on 2005 Census of Economic Establishments for which data was collected between 2001 and 2003. The results showed that 99% of these enterprises were microenterprises, employing less than 10 workers. Similar results can be seen through analysis of Labour Force Survey 2018.

[3] State of SMEs in Pakistan, SMEDA

[4] Of the 842,716 employers, only 14,115 (1.67%) are females.

[5] These results are based on a rapid survey of 410 young entrepreneurs across 18 countries and a wide range of sectors by Youth Co:Lab.

Employment Analysis

Those particularly vulnerable under the current situation are women workers (teachers, care workers, travel and tourism workers), elderly and those with preexisting health conditions, young workers, persons with disabilities, informal economy workers (including domestic workers and home-based workers) and self-employed workers like street vendors, taxi drivers and gig workers engaged with different digital labour platforms. COVID has affected livelihoods of domestic workers (8.5 million), home-based workers (4.8 million) as well as those working on roads, including street vendors (4 million). The concept of vulnerable employment generally includes own-account workers and unpaid family workers. Centre for Labour Research has also included ‘casually employed” (paid by piece rate or on daily basis) in the vulnerable employment. Those in vulnerable employment are 45.5 million which is equivalent to 76% of overall employment. More than 60% of non-agricultural employment is vulnerable by this standard.

The informality rate for non-agriculture sector is 72% which means that the non-agriculture informal sector employs 72% of the labour force. The total unprotected sector (a mix of agriculture and non-agriculture informal sector) is composed of 49 million workers, equivalent to 82% of the overall employed labour force. Only 1.8 million workers are registered with the provincial social security institutions.[1] While Employees Old-Age Benefits Institution (EOBI) has registered 8.6 million workers since its inception in 1976, the currently active insured persons[2] are 2.65 million only.[3] The current beneficiaries with the EOBI, receiving the old-age pension, invalidity pension or survivors’ pension, are only 448,000.

The gig or platform economy workers,[4] especially those providing geographically tethered services like transportation (Uber and Careem), delivery of items (Bykea)[5] and domestic work (Mauqa, Ghar Par) are worst hit. These digital platforms treat these workers as independent contractors, hence relieving themselves of any employment responsibilities towards these workers. Considering the fact that food delivery is permitted by the provincial governments even during the lockdowns, gig workers working with food delivery platforms like Foodpanda[6] are on the front lines of this crisis. They are delivering food to those self-isolating or practising social distancing. They are, in a sense, providing essential services during the times of lockdown. The government must also consider the impact of lockdowns on thousands of Uber/Careem drivers, Bykea partners, and domestic as well as maintenance workers engaged with other platforms.

As regards online or crowd work, Pakistan was ranked fourth among the top 10 countries in the world in terms of growth in earnings by freelancers, according to the digital money transfer service, Payoneer.[7] The Oxford Online Labour Index, Pakistan is home to the third-largest population of professionals related to the global crowd work gig industry after India and Bangladesh.[8] Its market share is nearly 11%.[9] On the other hand, while no clear numbers are available, there are tens of thousands of drivers and riders engaged with ride-sharing and delivery platforms.[10]

While Government-announced lockdowns in provinces have protected the jobs of “workers” in the formal sector requiring employers to pay full wages and not terminate any, the so-called “independent contractors” do not have access to any of these protections. Research already indicates that domestic workers, delivery persons (couriers), garbage collectors, and janitors, all part of the growing gig economy, are at the highest risk of being exposed to coronavirus.[11] Self-employed workers, especially gig workers, are facing the tough choice between exposure to the pandemic (getting sick and infecting families) and exposure to starvation (by not working and losing income). Self-isolation is a luxury for these workers.[12]

[1] “Barriers to Pay Equality in Pakistan” by ILO Islamabad Office

[2] For whom contributions are paid by active insured 43,000 employers/enterprises.

[3] EOBI Data, available through OP&HRD

[4] The platform economy distinguishes between two major forms of work: crowd work and work on demand via apps. Crowd work is performed online and is location-independent. It includes software development, data entry, translation services, etc. Examples are UpWork, Fiverr, and Freelancer.

‘Work on demand via apps’, on the other hand, matches the worker and the client digitally and the work is performed locally. Activities include transportation, food delivery and home services. Major platforms in Pakistan include Uber, Careem (transportation), and Foodpanda (food delivery).

[5] Bykea has over 30,000 daily wage earners working with it. It has launched a Rs. 7 million relief fund for its driver partners affected by the lockdown and suspension of services amid the coronavirus pandemic.

[6] Uber and Careem have also started delivery services in Islamabad and Lahore.

[7] Global Gig Economy Index 2019

[8] Online gig work is also affected by the pandemic. A preliminary analysis of Oxford Online Labour Index for Pakistan indicates a drop in demand for work in categories like clerical and data entry and creative/multimedia. Overall, the number of projects/tasks allocated to online workers in Pakistan between February and March 2020 has increased by 1.63% only.

[9] State Bank of Pakistan, in its first quarterly report for 2019, also recognized this increase in freelancing work and its impact of ICT exports, attributing this to “improved internet access to more than 2,000 cities across Pakistan; a large number of graduates entering the workforce; and government efforts to promote freelancing are the key factors behind this growth”. Payoneer also noted in its report that Pakistani youth is fueling gig economy explosion in the country and that Government investment in enhancing digital skills has helped create a skilled freelancer workforce.

[10] The Online Labour Index (OLI) is the first economic indicator providing online gig economy equivalent of conventional labour market statistics. It measures the supply and demand of online freelance labour across countries and occupations by tracking the number of projects and tasks across platforms in real time.

[11] The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk by New York Times

[12] The politics of Covid-19: Gig work in the coronavirus crisis

Actions to Take

While protecting workers and their families from this pandemic should be the first priority, demand-side measures are also needed to protect those facing income losses because of infection or reduced economic activity. There are three aspects of COVID-19 created labour market shock: the number of jobs is declining due to closures leading to increased unemployment and underemployment; the quality of employment is worsening due to lack of income replacement programs in the event of sickness or unemployment, i.e., lack of social protection; and it is disproportionately impacting the already vulnerable and marginalized including elderly, women, young, and self-employed workers.[1]

Based on the above aspects, the following actions are recommended to ameliorate the pernicious effects of COVID pandemic on the labour market:

Short Term Measures

Implement WHO guidelines at workplaces. To protect workers and minimize the direct effect of coronavirus. While Punjab and Sindh have already enacted occupational safety and health legislation, other provinces are still lagging. Work Councils, provided under the industrial relations legislation, as well as OSH Committees, to be constituted under the OSH legislation can play a role in awareness-raising on social distancing and other hygiene measures at workplaces. Health and safety provisions from Factories legislation should be applied earnestly in other provinces.

Protect employment through incentives. Those economic sectors and enterprises negatively impacted by the coronavirus, especially in the manufacturing and services sectors, should be protected through various incentive measures. Governments should ensure that workers suffer no wage losses due to quarantine or isolation.

The government can reduce or waive off payroll taxes (PESSI, EOBI) for three months (March-May 2020) to those enterprises who retain their workforce. The government may also announce time-bound tax relief measures for enterprises who announce job-sharing schemes. Similar financial benefits can be announced for all such enterprises which register their workers with social security institutions.[2]

Layoff vs termination. Labour legislation in Pakistan provides a procedure for laying-off workers in the event of a catastrophe or an epidemic. Under this, workers are granted 50% of their wages during the first 14 days of layoff. Instead of requiring employers to pay full wages, the government should enforce this provision of labour law. During the extended lockdowns, a portion of wages, at least equivalent to the minimum wage (17,500 per month), can be paid by the government through already available funding with PESSIs, Workers Welfare Fund and Employees Old-Age Benefits Institution.[3]

Compensate workers and enterprises directly. While BISP is focusing on low-income households, there is a need to focus on micro-enterprises, employing less than ten workers. Direct lump-sum compensation can also be provided to the self-employed workers. SMEs, facing financial difficulties, can also be supported through easier loans.

Provide Unemployment benefits. The government can start giving unemployment benefits (at least equivalent to a minimum wage of 17,500 rupees per month) to unemployed and initiating public employment programmes. Local government system can help in identifying individuals who lost their employment due to the enterprise closures or cancellation of public events.

Workers Welfare Fund, an attached department of Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource Development, has an available fund of 120 billion rupees. An unreconciled amount of 48 billion rupees of the Workers Welfare Fund is also available in the Federal Consolidated Fund which is managed by the Finance Division. This can be used to initiate the emergency unemployment benefits program in the country. Later on, the unemployment benefits can be based on the social insurance system where both workers and employers should contribute.

On 30 March, the Economic Coordination Committee approved 200 billion rupees of cash assistance for the daily wagers working in the formal industrial sector and who had been laid off as a result of COVID-19 outbreak. Based on a summary from the Ministry of Industries and Production, it has been estimated that nearly three million daily wage workers in the industrial sector have lost their jobs due to the pandemic induced mobility restrictions and must be paid a minimum wage of Rs.17500 per month. The estimated cost of this provision for daily wagers comes around to Rs. 52.5 billion a month.[4]

There is a flaw in this scheme as it is considering only the industrial sector without even referring to the services sector as well as the construction sector, which are the hardest hit sectors. Of the total 10.74 million casually employed workers (paid on daily, weekly or piece-rate basis), 1.82 million are in the services sector, 2.04 million in the agriculture sector and 4.09 million in the construction sector.

The government may establish an independent board to oversee the functioning and distribution of the fund, especially 200 billion rupees approved by ECC for the Ministry of Industries and Production, and the constitution of an expert group of professionals to prepare one-year plan to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on labour. Labour Welfare and Social Protection Expert Group, constituted under the Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety Division can also be reactivated in this regard.

Engage in social dialogue. Tripartite social dialogue, both at the federal and provincial level, must be initiated to develop sustainable solutions to the various workplace issues emerging in the wake of COVID-19. Pakistan already has federal and provincial tripartite committees whose online meetings must be called at the earliest to discuss issues of health and safety, paid sick leave and its extension, job losses, unemployment benefits, and issues of workplace discrimination and stigmatization due to infection. Representative organizations of social partners, Employers Federation of Pakistan (EFP) and Pakistan Workers Federation (PWF), have issued a joint declaration demanding constitution of a special tripartite taskforce in each province for consultations on collective action and assistance in the execution of the plans for economic and social recovery.

Medium Term Measures

Expand access to paid leave. While ensuring income security to those who are sick (quarantined or isolated) or are caring for family members. Paid sick leave is only eight days in Pakistan. For those registered with the provincial social security institutions (PESSIs), employment-secure sickness benefit is available for 121 days in a year; however, only 1.8 million workers are registered with PESSIs. Flat rate sickness benefits must be made available to the informal sector workers as well as self-employed workers.

Register workers with Social Insurance Institutions. BISP is adding 7.5 million more families in the system and plans to pay a sum of 12,000 rupees. Similarly, ECC has approved a budget of 200 Billion for formal sector workers. All these workers, irrespective of their work status, must be registered with the PESSIs and EOBI. Once this pandemic is over, special contributory social insurance schemes can be launched for self-employed, informal and agriculture sector workers.

Make social protection a fundamental right. Recently, the Ehsaas Policy Statement had mentioned the government’s aspiration to introduce a new constitutional amendment to move article 38(d) from the “Principles of Policy” section into the “Fundamental Rights” section. This change would make provision of food, clothing, housing, education and medical relief for citizens who cannot earn a livelihood due to infirmity, sickness or unemployment, a state responsibility. The time to introduce such constitutional change is now since healthcare, sickness benefits and unemployment benefits must be universally accessible. Federal Government has already announced Emergency Cash Programme of 12,000 rupees (3,000 per month for the next four months) to 12 million families (72 million individuals), to be covered under the Ehsaas Program.[5]

Long Term Measures

Give legal cover to the teleworking and flexible work. There is a dire need to give legal cover to teleworking and flexible work time arrangements, not only for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic but for the later times to reconcile work and family. Social distancing, a major tactic to curb the spread of coronavirus, can be done through telework. While some jobs, by their very nature, are difficult or impossible to do without the physical presence of worker at the worksite (like food and beverage workers, construction workers, law enforcement agencies), knowledge workers especially financial analysts, accountants, lawyers, software designers, scientists and engineers. Countries are using different flex-time and flex-location options to encourage teleworking.

Enact new legislation for microenterprises, employing ten or fewer workers. LFS 2018 already shows that 26.89 million are working in the micro-enterprises in the non-agricultural sector. Shops and Establishments legislation is already there; however, it is not solely for micro-enterprises. A simplified single labour code for micro-enterprises, with fewer requirements and ease of compliance, must be enacted at the earliest.

Regulate the gig economy. Deregulation of the gig economy is hurting the economy and society as a whole by producing a whole generation of unprotected workers. Gig economy workers are part of a larger informal economy without access to any social protection benefits. There is a dire need to make the gig economy fairer, in line with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. Requiring digital labour platforms to register their workers aka independent contractors with social security institutions and EOBI could be the first step in that direction.

Of all the informal economy workers, the gig economy workers are the easier ones to regulate as their work is already documented, more visible and structured than domestic or home-based work.

Will it be enough?

That’s too early to tell. And it might even get worse. Quite unlike other calamities like war, floods, hurricanes or earthquakes, this pandemic is still happening and spreading wildly. The policy responses must ensure that support reaches the workers and enterprises which deserve it the most, including low wage workers (especially those earning less than 20,000 per month), the self-employed and micro enterprises.

Basic labour protections, adequate living wages, decent working hours, social protection and safe workplaces should be available to everyone irrespective of contract/employment status. Social protection should not be a luxury; it should be available to everyone!

[1] https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_738753.pdf

[2] President Employers Federation of Pakistan, Mr. Majyd Aziz, in his op-ed, has given certain suggestions to deal with the current circumstances: allow individual enterprises to establish an Emergency Fund which would include the amount due to be paid to employees on account of bonus for the current year; amount distributable among employees on account of Workers Profit Participation Fund for the current financial year; the amount of 2% of profit payable on account of Workers Welfare Fund; suspending amount payable to the PESSIs and EOBI on account of their monthly contributions and transferring it to the Emergency Fund; and adjusting employees leave balances for the current and next years’ leave entitlement

[3] Instead of making employers bear all the cost of closures due to lockdowns, State must pay a reasonable portion of wages to workers. https://voxeu.org/article/economics-wage-compensation-and-corona-loans

[4] PR. 283, Finance Division, Government of Pakistan

[5] https://dailytimes.com.pk/587305/sms-service-launched-to-provide-emergency-cash-grant-to-needy/ ; http://www.radio.gov.pk/09-04-2020/disbursement-of-cash-assistance-under-ehsaas-emergency-cash-program-begins-today